Curating Kant. Illustration by author.

Curating Kant. Illustration by author.

Curating Kant. Illustration by author.

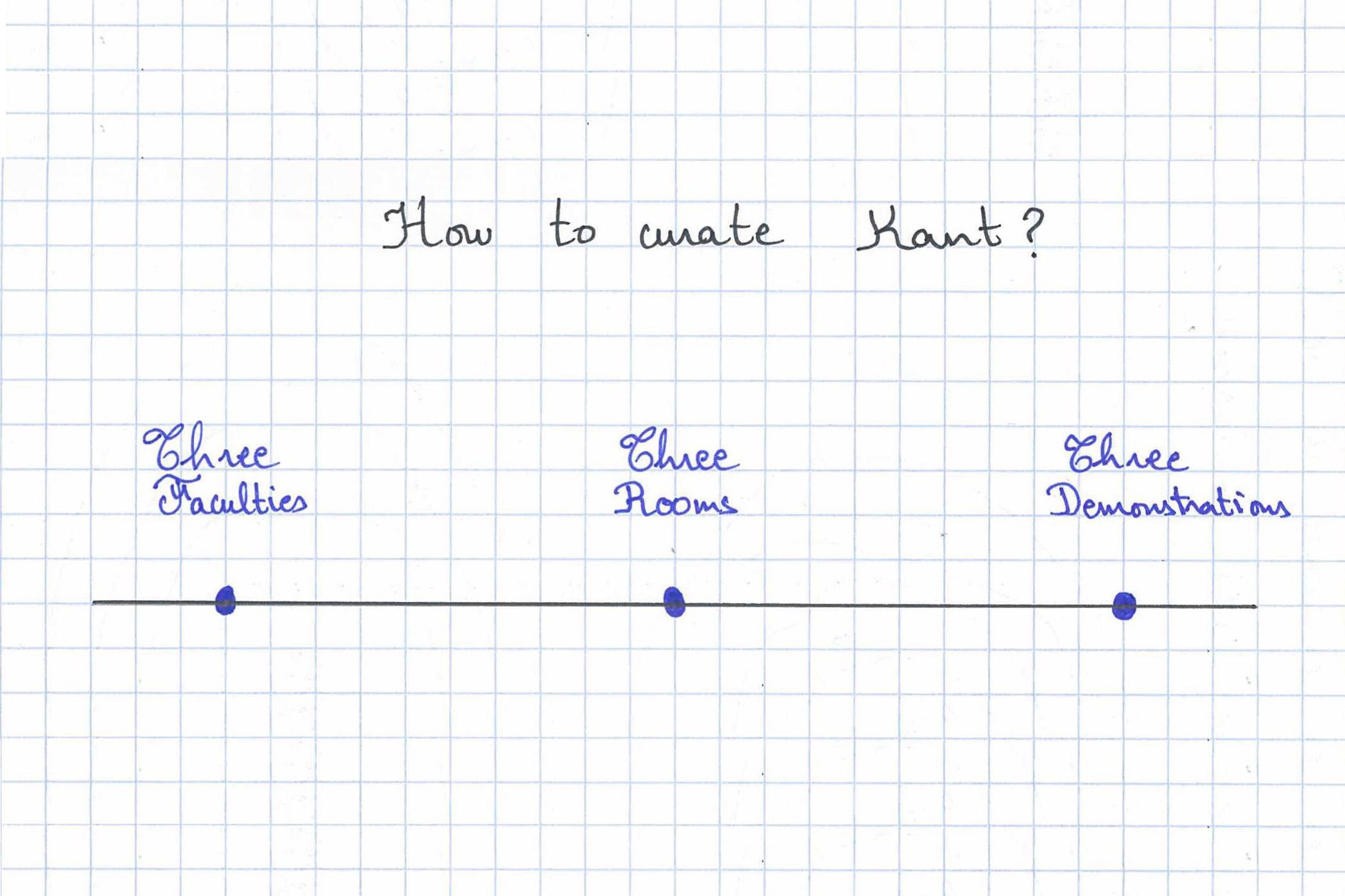

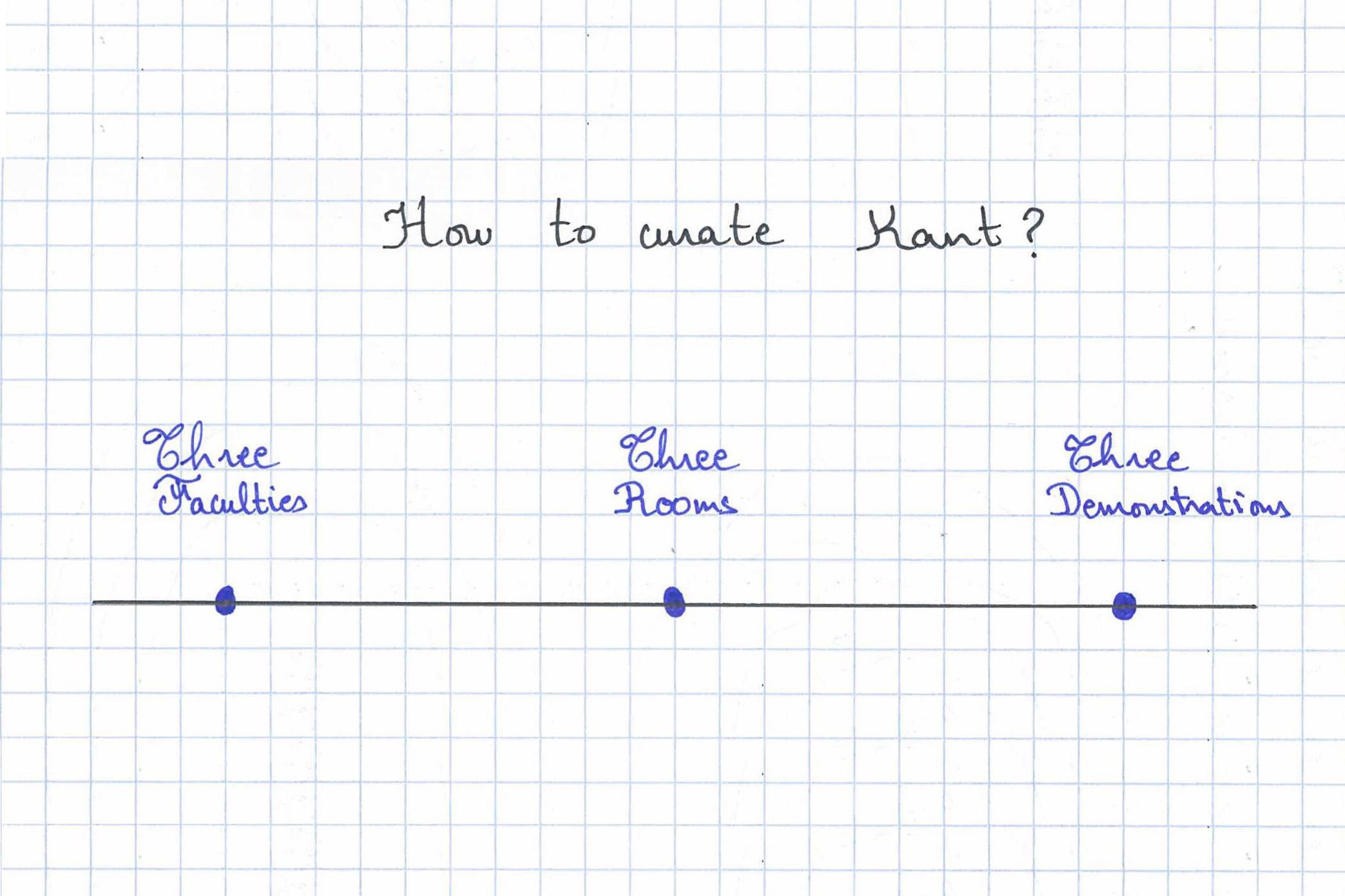

1. Exhibiting thought. If you need to write your exhibition, then you might as well find a publisher. ‘Show don’t tell’ might be the most important instruction when making an exhibition. Instead of words, look for visuals, drawings and objects that show your argument. Make it pleasant and to the point. Think of your argument as a space that your audience can walk into.

2. Like second nature. It is difficult, almost impossible, to imagine a world without exhibitions. From the selection of items on a living-room shelf to that National History Museum, the impetus to select, arrange and display belongs to all.

3. The medium is the message. Put simply, exhibitions present ideas and concepts to the public by configuring objects in a space. Digging deeper, they are a little bit more intriguing. They also have to mediate those ideas. While exhibitions showcase an idea, this also happens by carefully selecting works to prove that idea and by finding adequate ways to invite a public debate of that very idea. How can we understand this ‘triple factor’? Curiously, ‘demonstration’ is synonymous to exhibition-making in a very intimate way. It is a polysemic term which has three different meanings, all of which relate to exhibition-making, namely a practical presentation of how something works, an orderly proof of the existence of something, and a public gathering to express people’s views. These three meanings neatly align with an exhibition’s fundamental pillars of space, artefacts and the public. An exhibition is a demonstration in the full sense of the term.

Immanuel Kant. Illustration by author.

4. Since 1781. Many curators and exhibition makers are unaware of the debt they owe to the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Writing at the end of the Enlightenment, he invented a method which allows our ideas to become exhibitions. He called this the ‘transcendental method’. Not to be confused with ‘transcendent’, which means ‘beyond’, transcendental is more about figuring out the limits, sources and extent of one’s idea.1 It is a ‘tribunal that is no other than the critique of pure reason’.2 Effectively, Kant is drawing a position from which an idea can carefully judge itself. The spatial undertones to his method should not be overlooked. A conceptual idea that as yet had an immaterial existence suddenly becomes something that exists in a space, something that we can observe, judge, reflect on, even walk into. ‘One could say that the curator establishes an experiment in the form of an exhibition, which enables his/her hypotheses to be publicly demonstrated’.3 As curators, we have in essence been setting up these ‘experiments’ and ‘tribunals’ by exercising this transcendental method. Not to be missed is the manual that comes with this reflexive apparatus: Critique of Pure Reason, authored by Kant himself.

5. I Kant understand. A universal known truth about Immanuel Kant is that his writing is difficult to understand. He wrote stiff, lengthy volumes full of highly technical terms. How would you make an exhibition about Kant? Aphorisms could be one way to go about it. The experience of reading these fragments responds to an exhibition’s spatial articulation. Reading about Kant that way feels like walking into an exhibition, a spatial demonstration, of his work.

6. Call for curators. In 1984, Jean-Francois Lyotard co-curated Les Immatériaux [The Immaterials] with Thierry Chaput for the Centre Pompidou. It was not just an exhibition about postmodernism. It was postmodernism transformed into an experience through the format of an exhibition. He had already written books, sat for interviews and lectured on the topic several times before. Now, he transformed an immaterial theory into a material experience. The French philosopher became a curator, trading a blank page for a white wall. Lyotard was also an ardent commentator of Immanuel Kant’s aesthetic theories and responded to the latter’s call for a transcendental method.

7. Down the rabbit-hole. Why would I visit an exhibition about a topic I know inside-out? Will something change when I go?

8. A reflexive apparatus. Immanuel Kant wanted nothing more than to secure an autonomous path for reason. He invited us to ask ourselves not ‘What do I know?’ but ‘What can I know?’: ‘It is a call to reason to undertake anew the most difficult of all its tasks, namely, that of self-knowledge.’4 This introspective move creates a shift in perspective, a new standpoint that turns static knowledge into the dynamic ability to know. In the case of exhibitions, they don’t provide us with direct answers but rather invite us to recompose them. In that process, they give us the opportunity to practise the question ‘What can I know?’. They are also opportunities to experiment with our relationship to that knowledge because seeing and thinking about artworks and artefacts happens in tandem. This emphatically transforms our relationship to knowledge: walking through the exhibition, we are now the ones undergoing that public demonstration of knowledge.

1 Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Norman Kemp Smith (London: Macmillan Press, 1996), ‘Preface to First Edition’, A xii, p. 9.

2 Ibid.

3 Sue Spaid, The Philosophy of Curatorial Practice (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), p. 202.

4 Kant, Pure Reason, A xi, p. 9.

Curating Kant. Illustration by author.

9. Meet me at the exhibition. The exhibition is where the spectacular meets the epistemic. We learn and think differently in that setting. Unlike a classroom or an office, our bodies move. Unlike a textbook or a lesson, the object in question is fully present. This format invites a different reception of knowledge, where perception and conception happen simultaneously. The exhibition operates at the intersection of the aesthetic and the cognitive.

10. Artist biography. Across all his three critiques, his main body of work, Kant was an artist of thought who took concepts, ethics and aesthetics seriously. Beginning with Critique of Pure Reason, Kant invites us to question our own knowledge. As the philosopher moves to ethical concerns in Critique of Practical Reason, he analyses desire in relation to morality. Finally, in Critique of Judgment, Kant turns his attention to the power of judgment itself, meaning the feeling of pleasure and displeasure.

11. Enter here. Many exhibition-makers display their curatorial text at the entrance, the threshold of the exhibition. There, the audience awaits to reconstruct the correspondence between text and space.

12. Know your history. In 1543, Vesalius performed lessons on anatomy by exhibiting a human body in the centre, inviting an audience of minds around that body. With an opportunity to look at a body inside out, this was a demonstration of how it works. While Vesalius was giving an explanation of anatomy, in that spatial setting, learners were also shown anatomy by walking around a human body on display. Also in 1543, Copernicus had proved that the sun was at the centre of our system, with the Earth revolving around it.5 Kant narrates the Copernican Revolution as such: ‘He [Copernicus] tried whether he might not have better success if he made the spectator to revolve and the stars to remain at rest.’6 It is an interesting coincidence for exhibition-making that both these events happened in the same year. Both events are shaped by similar theatrics where the subject watches, from a distance, a presentation of knowledge. Fast forward to today’s museums and galleries, and the dynamics in the exhibition space remain the same. People still walk around fixed artefacts whose display accounts for material and visual manifestation of knowledge.

13. The show must go on. The term ‘demonstration’ stems from the Latin prefix de, which means ‘from’, and the verb monstrare, which means ‘to point out, show or reveal’. In other news, Vesalius curated Anatomy Lesson in 1543.

5 Georges Canguilhem, L’homme de Vésale dans le monde de Copernic: 1543, from the lecture series commemorating the 400th anniversary of the death of Andreas Vesalius, 1964, Belgian Royal Academy of Medicine.

6 Kant, Pure Reason, Bxvii, p. 22.

Vesalius/Copernicus. Illustration by author.

14. If it weren’t for Copernicus… What happens to an object once it is on display in an exhibition? Granted, its physical properties won’t change. It remains of the same height, colour and weight. However, now that it is subjected to the exhibition’s concept, it matters not what it is in itself but rather what the exhibition makers want us to know about it. Take for instance a displayed copy of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. It has been opened to the first page, with its iconic first sentence: ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.’ While the museum label might provide general information about the book, what matters most is the actual page selected for display. Kant would have appreciated this mindset: ‘We have complete insight only into what we can ourselves make and accomplish according to concepts.’7 How things seem to us, how we organise them through the concepts we make, is more important than what they are in themselves. What matters is ‘What can I know?’. In fact, what we need to know about A Tale of Two Cities is all in its first words.

15. You can’t count on experience. The Kantian subject is a subject of reason. It matters not what they experience but rather how they can integrate experience into their ideas. That is one of the main concerns of Critique of Pure Reason.8 For Kant, you only integrate from experience what you can understand according to certain principles. In that sense, the exhibition is a very Kantian method. It is a framework in the service of experience which offers the audience a structure with which to understand what they are physically experiencing, meaning the artefacts and artworks on display.

16. Operation theatre. Vesalius’ students were not there to experience anatomy. They were there to understand it. The point is to stay at a remove from experience.

17. A priori. Perhaps like many curators, Kant begins the first critique, his ‘exhibition’ of reason, by speaking about space. He says something about the role of space in our understanding of experience. Space is just there, he says, but it is necessarily there for a reason because without it, experience itself would be impossible.9 He terms it a priori. It is a condition which renders possible the representation of objects in our minds, the form on which cognition is built. The exhibition space, like a gallery or a museum, functions like an a priori too. Let’s imagine two scenarios. In the first, you are walking down the street and you see a copy of Homer’s The Odyssey, then a life-jacket, followed by an English dictionary. In the second scenario, you walk into a gallery in which you encounter three display cases with the three items mentioned above – The Odyssey, a life-jacket and the dictionary. Which of the two scenarios makes it easier for you to understand the concept of migration? Each of these objects does not necessarily fall under the concept of migration. Yet once they become neighbours in the exhibition space, they begin to make sense to us in a new light. The exhibition space prepares us for the experience and understanding of the curatorial concept.

18. Display strategy. The distance between the objects is a condition for their appearance.

19. Mind the gap. Have you ever wondered why we can’t stay too close to the display cases? The artefact’s safety is one obvious concern. But this notice isn’t just for the sake of the artefact, it’s also for the audience. Of course, the closer you are, the less you might see of the whole object, and thus the less you will know. This spatial setting creates ordered relations, thus turning the objects into candidates of conceptualisation in our minds. The critical distance between the viewer and the display enables reflection and understanding.

20. The power within. Faculty.

21. Count your steps. We enact a different viewpoint onto the displayed works as we walk around them. With each step away from the work, we discover that we know. This transcendental distance is like geometry for subjectivity.

22. In lieu of an abstract. What happens between the written exhibition concept and the physically installed exhibition? At that moment, curators, artists, exhibition designers, scenographers and art handlers direct their attention to the floor plan. A diagrammatic expression of the exhibition and the artworks or artefacts are carefully annotated on it. Some exhibitions even print out a version of it for the audience. Beyond ‘Place this here’ and ‘You are here,’ what does the floor plan do? Kant might as well have invented the exhibition floor plan. He calls it a ‘schema’. Not only a noun, it is a method or procedure for producing a mental image for a concept.10 In other words, the floor plan allows its reader to run through the exhibition correctly. Like any schema, it helps us figure out what the exhibition has to say and the connections between the works. Beyond summarising, the floor plan serves the job of mediating the concept into the final exhibition. Once you see it, well, you get the gist of it.

7 Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1987), 384, p. 264.

8 Kant, Pure Reason, Bxvii, p. 22.

9 Ibid., A24/B39, p. 68.

10 Ibid., A140/B80, p. 182.

Exhibiting Kant. Illustration by author.

23. Do not touch! There are two types of spectators at an exhibition: those who keep their hands in their pockets, and those who keep pointing their fingers at the different things they see. One keeps to herself, and the other seeks the community of works around him. Perhaps these mirror two different citizens – those who join demonstrations versus those who sit them out.

24. Exhibition means معرض. As public institutions, museums are required to serve members of the public. This means working towards enhancing the accessibility of knowledge. The increasing collaboration between educators and curators is an example of this, as is the outreach through public programmes that involve the young and the old. In fact, even a curator’s mandate holds an axiomatic quality: ‘To serve the public good by contributing to and promoting learning, inquiry, and dialogue, and by making the depth and breadth of human knowledge available to the public.’11 In Unhealed, an exhibition about experiences of the Arab Spring of the early 2010s, the curators Abir Boukhari and Joe Ljungberg at Moderna Museet in Malmö, Sweden, shared their texts in Swedish, English and Arabic.12 The first and second languages follow the standard routine of accessibility in a globalised world. You will encounter this in many other museums. However, in a city with a large migrant population from the Arab world, and with a topic about that very geographic location, the choice of Arabic serves a local and focused idea of the public good. Curating means something like anticipating the public good and acting to achieve it.

25. Job description. ‘A curated selection of aged cheese’ is not wrong but imprecise. ‘Curate’ comes from the Latin curare, which means ‘to cure’. Like medical professionals, curators are caretakers, paying attention to the artefacts, the display and the audience. The British Museum even calls them ‘keepers’. Theirs is a mandate of care.

26. No harm done. Even those who are not familiar with ethics might have heard of the term ‘categorical imperative’: ‘So act that the maxim of your will could always held at the same time as a principle of a universal legislation.’13 It is another Kantian inheritance which cuts across many fields. In the second of his critiques, Critique of Practical Reason, Kant is concerned with how action can be guided by reason. Moving forward, Kant will ask, what can I do with what I know? Are my actions such that I could accept them for myself? The debate around the display of human remains in museums might be a case for Kant’s categorical imperative. Choosing not to display human remains falls under the universally accepted idea that one ought to respect the deceased, hence the universal ‘Rest in Peace’. To apply a moral law such as the one Kant cites, we need to cross from the realm of reason to the realm of the sensible. Imagination helps us make that crossing. By producing mental images of the maxim, like a mental exhibition, we begin a self-examination. ‘Would I accept my remains in a gallery centuries from now? Would the mummy want to be displayed? Would I be acting according to the moral law if I were to display a mummy in the gallery?’ In a curatorial context, we recall ethical questions through imagination of oneself and of others. An exhibition’s moral behaviour rests on this feeling for others. It imagines an exhibition, its audience and reception before they even happen.

27. Put yourself in my shoes. Common sense in an exhibition is not just keeping glass objects off the edge of the table. It evokes what Kant calls an ‘enlarged mentality’ by which we put ourselves in the thought of everyone else.14 It is ‘a power to judge that in reflecting takes account in our thought, of everyone else’s way of presenting something, in order as it were to compare our own judgment with human reason in general’.15 It requires us to imagine what it would be like to feel and think from another point of view. The enlarged mentality needed in the context of the exhibition continues the work of Kant’s transcendental. From here, an interesting scenography begins to develop. Imagination works towards the intersubjective and makes thinking larger. Hannah Arendt recognised this aspect of Kant’s aesthetics as highly political, ‘by the force of imagination it makes the others present and thus moves in a space that is possibly public, open to all sides… To think with an enlarged mentality means that one trains one’s imagination to go visiting.’16 Common sense is an exhibition one can visit in order to experience those new points of view. As an enlarged mentality where sincere community and communicability happen, exhibitions are public in a powerful sense of the term.

28. Your opinion matters. Interactive exhibitions were a remarkable paradigm shift from the encyclopaedic displays that preceded them. Today’s curatorial and display strategies acknowledge the audience as an active one. This is where Kant meets Jacques Rancière. ‘Emancipation begins when we challenge the opposition between viewing and acting,’ wrote the contemporary French philosopher.17 Today’s display strategies encourage a mobile and agile gaze which questions the gap separating the object and the subject, the museum and the public. Then the latter enters the museum as an active interpreter of the display, joining what they know with what they do not know. Emancipation perfumed with Kant’s ‘What can I know?’. This is the enlarged mentality of the emancipated spectator.

29. If a public square were an exhibition. ‘Public’ is a key term in Kant’s philosophy. Not only is it related to politics but it is an adjective he uses to qualify reason with freedom. In ‘What Is the Enlightenment?’, it qualifies an exercise of reason whereby people can think for themselves, shake off the opinions of others and guide reason with moral freedom.18 It entails a reason that is aware of its limits and can situate itself vis-à-vis others. Perhaps exhibitions of the nineteenth and early twentieth century can be challenged based on this question: how do they account for a ‘public use of reason’?19 While reductive objectification remains a valid problem with regard to displays and exhibitions of that period, thinking through Kant’s public shifts the conversation to the audience’s ability to reason as a measure for good exhibitions. What good is an exhibition that rehashes solidified opinions without leaving room for other thoughts? What good is an exhibition that does not produce freedom? That remains true today when curators guide the audience too rigidly, for instance with excessive textual interventions. A good exhibition becomes a space where we can orient our thoughts with freedom and take the risk of thinking against accepted notions. To do so in public is akin to taking part in a demonstration of reason that replaced public squares with museum halls. Good exhibitions are judged by the exercise of reason they encourage.

11 John Mayer et al., A Code of Ethics for Curators (Washington, DC: American Alliance of Museums/American Association of Museums Curators Committee, 2009).

12 Unhealed, exhibition catalogue, curated by Abir Boukhari and Joe Ljungberg (Malmö: Moderna Museet, 2024).

13 Immanuel Kant, Critique of Practical Reason, in Practical Philosophy, ed. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 5:30, p. 164.

14 Kant, Judgement, 294, p. 160.

15 Ibid.

16 Hannah Arendt, Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), p. 43.

17 Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator, trans. Gregory Elliott (London: Verso, 2009), p. 12.

18 Kant, ‘Answer to the Question: What Is the Enlightenment?’ in Practical Philosophy, ed. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 8:36, p. 17.

19 Ibid.

30. Missing guidelines. At times, exhibitions come to resemble kindergarten classrooms. More art and less writing on the walls.

31. Senses and sensibility. In Greek, aesthesis (‘aesthetics’) meant the senses. It refers to the eyes, the ears, the nose, the skin and the tongue. An experience of the world bathed in sensibility.

32. Visitor experience. In 1997, we went on a school trip to the Musée de L’Orangerie in Paris, where we saw Monet’s Nymphéas [Water Lilies]. That is my earliest memory of going to an exhibition. As we head back to the classroom, we discuss the landscape we had seen and the colours used by the artists, noting how they painted dots, which adults call ‘impressions’. Then we went on to paint in a nearby garden. It was all impressive for the five-year old I was. One of the reasons I still remember that day is because of the oval-shaped space. Even when I returned as an adult, I could still feel impressed. Today, I can realise that the way the Nymphéas were exhibited did the work of demonstrating what the impressionist movement means. The shape of the room lends itself to the artist’s brushstrokes, the skylight allows us to appreciate the importance of light in Monet’s work, and the whole experience is one of immersion and contemplation, as though I had experienced Monet’s artistic vision without recourse to a concept. While I’ve read and studied the impressionist movement, the exhibition remains what shaped my knowledge of the topic. My mind cannot disengage impressionism from that initial experience of the Nymphéas.

33. In the I of the beholder. By the time Kant had written his Critique of Judgment, he was no longer convinced that there was a science of taste. However, he contended that judging was an act of understanding, a cognitive power which ranks high on the Kantian scale. An aesthetic judgment is a reflection of how a sensation has affected our mental state.20 This means associations between sensible representations and abstracts concepts, where the first satisfies the second. Sensibility might not be a foundation for understanding, but it can nevertheless inspire it.

34. Please be seated. Kant on what happens to us during an aesthetic experience: ‘We linger in our contemplation of the beautiful. … The way in which we linger over something charming that, as we present an object, repeatedly arouses our attention, the mind is passive.’21

35. Benefits of going to an exhibition. In 2018, the Montreal Museum of Fine Art accepted medical prescriptions for free visits to the museum.22 It seems the medical community is recognising the psychological benefits of visiting a gallery. Immanuel Kant, for his part, defended the cognitive benefits of going to see fine art in his Critique of Judgment, in which he analyses the faculty of feeling pleasure and pain. He distinguished between two types of art, agreeable art and fine art. Agreeable art gives us pleasure through sensations. In contrast, fine art sources pleasure as ‘ways of cognising’.23 Enjoyment isn’t the point for Kant; what matters is that ‘this pleasure must be a pleasure of reflection’.24 No one enters the exhibitions expecting a purely didactic lesson. Instead, we find pleasure in retracing by ourselves the configuration of objects ahead of us, something like connecting the right stars to find the constellation. This is what Kant calls ‘reflective aesthetic judgements’, whereby we move from the particular towards the universal.25 Even walking around the exhibition implies this reflective incremental or sequential processing of its works. Every step gets us closer to piecing things together. Elsewhere, Kant calls this excitement a ‘mental agitation’.26 Reflection gets its adrenaline rush, hence the ‘pleasure of reflection’. Aesthetic reflective judgements elevate thinking into an emphatic experience.

20 Kant, Judgment, 223, p. 412.

21 Ibid., 223, p. 68.

22 ‘Montreal Museum Partners with Doctors to “Prescribe” Art’, BBC, 26 October 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-45972348.

23 Kant, Judgment., 305, p. 172.

24 Ibid., 305, p. 173.

25 Ibid., 179, p.18.

26 Ibid., 247, p.101.

Understanding Kant. Illustration by author.

36. Benchmark. A museum without benches doesn’t promote aesthetic experiences (nor comfort!).

37. Free play. Imagine an exhibition with Tutankhamen’s golden mask and Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa with her hidden smile. Two iconic works under one roof. A spotlight is directed on each one to frame its singularity. They shine and say ‘I exist’ or ‘look at me’. How will you react to that? Naturally, your eyes move in different directions. You might even catch yourself pointing a finger here and there. Each object is teasing you and calling for attention. Kant’s explanation for this is the ‘free play’ of our cognitive faculties of understanding and imagination, which represents the senses. In an ordinary experience, we understand what things are by subsuming the particular object under the general concept it belongs to. In other words, the first is a mask and the second a painting. During an aesthetic experience, however, each object wants to be recognised for its particularity. ‘Am I really just a mask to you?!’ Our cognitive faculties are suspended as they enter in a relation of ‘free play’. We are caught between understanding and imagination. For Kant, the particular object lingers longer with us, before, if at all, a general concept can be found.27 The same happens in the exhibition: we attend to objects differently by withdrawing from our habits of quick judgments. Through the exhibition format, thinking happens in aesthetic terms. Indeed, we linger, we play with the objects on display.

38. I’ll know it when I feel it. While exhibitions can be discursive, meaning that they partake in an affirmative presentation of knowledge, we can also approach them as instances where the definition of knowledge is being complicated in a good way. It also becomes a feeling. Thinking of curators working to implement Kant’s aesthetic reflective judgements on the level of their exhibitions as a whole, an expanded understanding of a demonstration emerges. Knowledge claims, like the exhibition concept, are being exposed, tried (as in put on trial) and tested by the public. We see it, walk through it and come out with our own judgments. In this context, knowledge is not a fait accompli but earned, somewhat like an achievement, ever so close to a demonstration of reason. This highlights the exhibition as an intellectual sensibility induced by aesthetic experiences. That experience becomes an emphatic proof of the hypothesis on display. Aesthetics, as used by the exhibition, is enacted as a mode of knowing.

27 Ibid., 222, p. 68.

Transcendental Games. Illustration by author.

39. Before you leave. So that you may always remember the experience, these mnemonic items are suitable for all ages. Toys for the young, decorative items for the old. Critique of Pure Reason is now available as a maquette of the exhibition floor plan so that you too can re-create an exhibition of the exhibition. To think twice about your local museum’s display of artefacts and to further your thoughts on Critique of Practical Reason, our team has selected books on institutional critique and decolonising museums. Please consider these foldable benches for your next aesthetic experience, they come with a storage pocket for Critique of Judgment. Our gift shop is truly Kantian in spirit. It operates window shopping as some sort of transcendental method, enacting distance but without reflection.

40. Keeping up with the Kantians. How often did the German philosopher visit museums and galleries? We don’t know. What remains is the exhibition as a transcendental. He created a mental space for the articulation and demonstration of an idea. We simply followed by building it.

41. Thank you for visiting. If you could read about a topic, then why bother going to an exhibition about it? An exhibition is a setting that offers a unique relationship to knowledge, whereby the latter is seen, felt and owned. A demonstration in the full sense of the term. The measure of an exhibition, its litmus test, is not what I know coming out of it but how it has enabled me to know. It renews the possibility of cognition, allowing makers and visitors to restructure their thoughts. Here lies their methodical quality. Just as any method holds the promise of success, the exhibition as a method holds the promise of experiencing knowledge.

Farida Youssef, “Maxims for Curators”, Metode (2026), vol.4 ‘Exhibition as Method’