Leaving the room, I notice the silence that follows collective reflection. The traces of dialogue, movement, and hesitation still seem suspended in the air. Walking through these rooms, I begin to think of curating context as inseparable from the idea of exhibition as method. Both are temporal, evolving, and situated ways of thinking—not fixed frameworks, but ways of learning through doing, of sensing through relation.

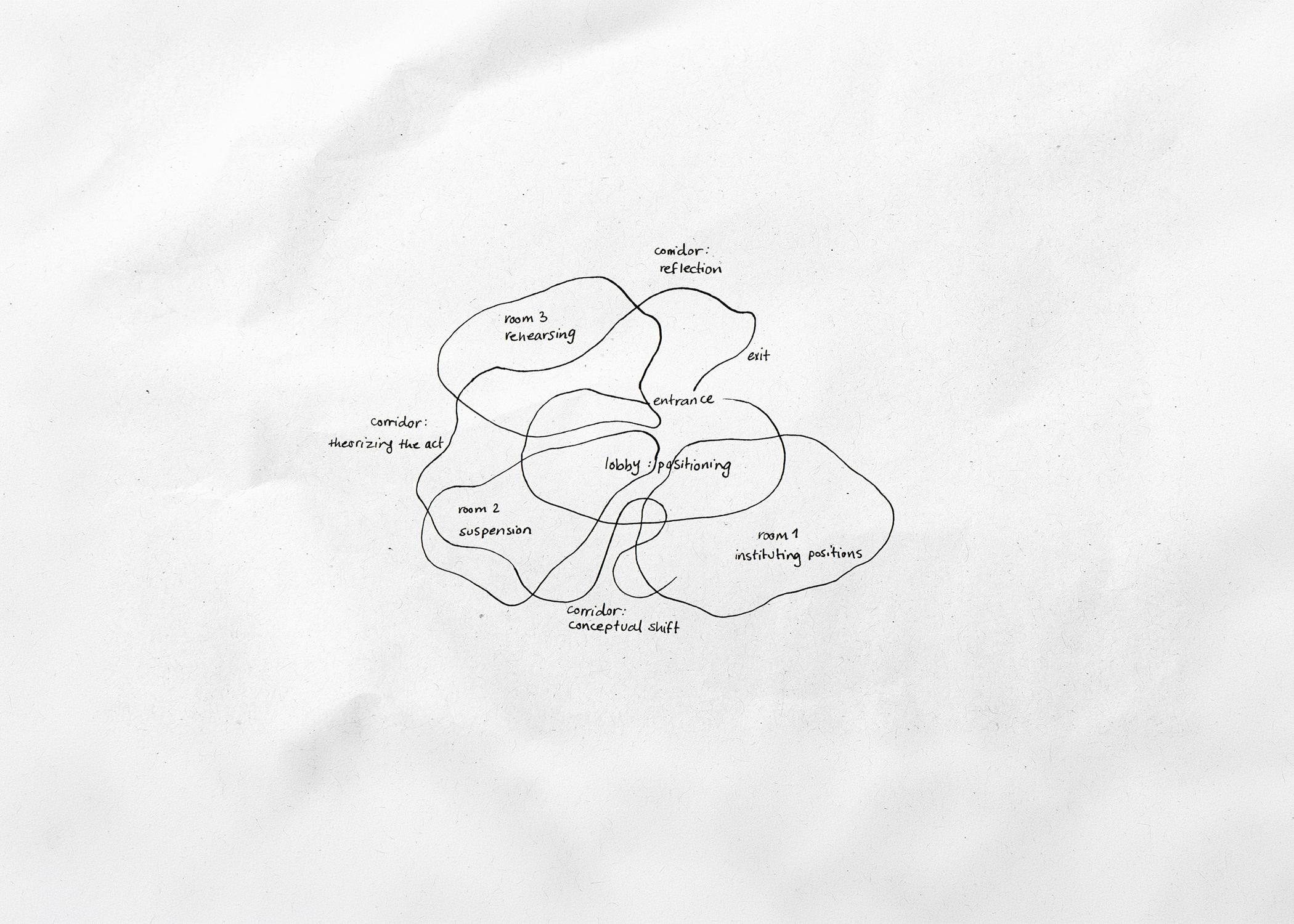

These three projects operate through distinct forms, yet they share a methodological commitment: to curate context as a way of making power relations visible, of suspending resolution, and of creating conditions where subjectivity can be exercised collectively. The exhibition, in this sense, becomes more than a format of display. It turns into a method for research, for thinking collectively, and for encountering difference. Through the rooms I have just described, I approached curating context from the position of an artist: as a way to arrange relations, to hold space for the unexpected, and to anticipate what does not yet exist. These three aspects together form what I now understand as a methodology—a way of practicing the exhibition as a site of inquiry.

Composing relations

Returning to The Living Room project, the tangled relation between host and guest becomes central. A room is set for people to come, sit, eat, drink, and talk, yet what stands at the forefront is the question of who hosts that room—the artist, the mediator, the institution, or the collective—and how each of these positions carries its own social implications. Reflecting on the dynamics of their position in society, whether as host or guest, reveals the shifting power relations embedded in acts of gathering, belonging, and representation. To curate context here is to ask what forms of belonging or exclusion are produced in society. It is also to understand how the act of hosting shapes participation, authorship, and the experience of being together.

During a discussion as part of An Experiment on Agency, one of the activations (a session held with a group of teachers), a participant began to speak, her voice trembling: “How can I raise a question around agency in my classroom, where Latvian, Russian, and Ukrainian students are sitting next to each other?” What followed was not an attempt to solve her question but a shared effort to map what she called the ecosystem of impossibilities—the limits of action and speech within lived, conflicted realities. It was a moment when subjectivity asserted itself precisely through its contradiction with the logic of the work, exposing how the attempt to curate context can itself surface what cannot be easily reconciled or contained.

Hosting the unexpected

The discussion that unfolded in An Experiment on Agency revealed how the exhibition as a curated space can never be fully contained or predicted. Even with carefully structured frameworks, what takes place within them often escapes intention. The teacher’s trembling voice and the momentary tension shifted the direction of the conversation entirely. It was no longer about the work as designed, but about what the situation had enabled to surface. In that instant, the project ceased to represent a question and became the question itself.

Curating context in an exhibition, in this sense, is also about leaving space for what cannot be foreseen. It is about constructing environments where experiences may unfold in ways that challenge both the work and its maker. In her essay “Beyond the Era of the Object: Towards the Aesthetic of Anti-commodification,” Cecilia Sjöholm emphasizes that “works of art present particular forms of agency, and are less interesting for what they are than for what they do.”15 She describes how a work of art can “represent a reckless mode of being in terms of its sensible appearance and spontaneity that kills the predictability of aesthetic forms.”16

The exhibition, therefore, can open a space for something to happen that neither artist nor audience could have entirely anticipated. This openness introduces a particular kind of vulnerability. The curator or artist who works with the exhibition in such a way must be ready to relinquish control, allowing the work to become porous to the social, political, and emotional realities that enter it. The event in Riga reminded me that what happens in such a space is never entirely of one’s making; it depends on those who inhabit it. The exhibition as a method of curating context thus becomes a practice of responsiveness. It is about hosting without knowing what will arrive, and about recognizing that the unexpected can itself be a form of knowledge.

Returning to the second room, In Vitro, I am reminded that the moment of rupture, the moment of the unexpected, is not necessarily spatial, physical, or discursive. It can also be narrative, or a stance taken toward a subject. In the sci-fi film by Sansour and Lind, an intentional reflective suspension is created—a space in which to dwell within uncertainty. The film’s unexpected flow of narrative pushes us to reimagine our relations to history, to the present, and to the future.

Anticipating the yet-to-come

If the unexpected breaks into the present, anticipation gestures toward what has not yet arrived. To curate context is also to work in the register of the possible—to prepare a ground for what might emerge. Then the exhibition does not only respond to a situation but anticipates its unfolding. It looks toward what could take shape through collective thought and encounters.

Raqs Media Collective, working as artists, curators, and philosophical agents, describe curating as “an act of anticipation.” For them art becomes a place as it gathers layers of unresolved relations and tensions to itself. In this gathering, distinction between different kinds of protagonists, between the unfinished and the finished, between art and non-art, spectator and participant, are held in suspension.17 For Raqs, the curatorial today stands as a critical protagonist—a site—for exploring the potential of this moment.18 It suggests that the exhibition is not a mirror but a threshold: a porous interface between what is and what might still come into being.

This sense of anticipation extends to how participants inhabit a work. Maria Magdalena Malm, in conversation with Elvira Dyangani Ose, reflects on how a work of art can create a context that “affects its participants by allowing them to become subjects.” She clarifies that this does not mean subjectivity can only emerge in participatory practices, but that certain contexts can enable such experiences of becoming.19 This distinction feels crucial. It shifts the focus from representation to activation, from displaying subjects to creating conditions where subjectivity is exercised and shared, and therefore the anticipation for yet-to-come can happen.