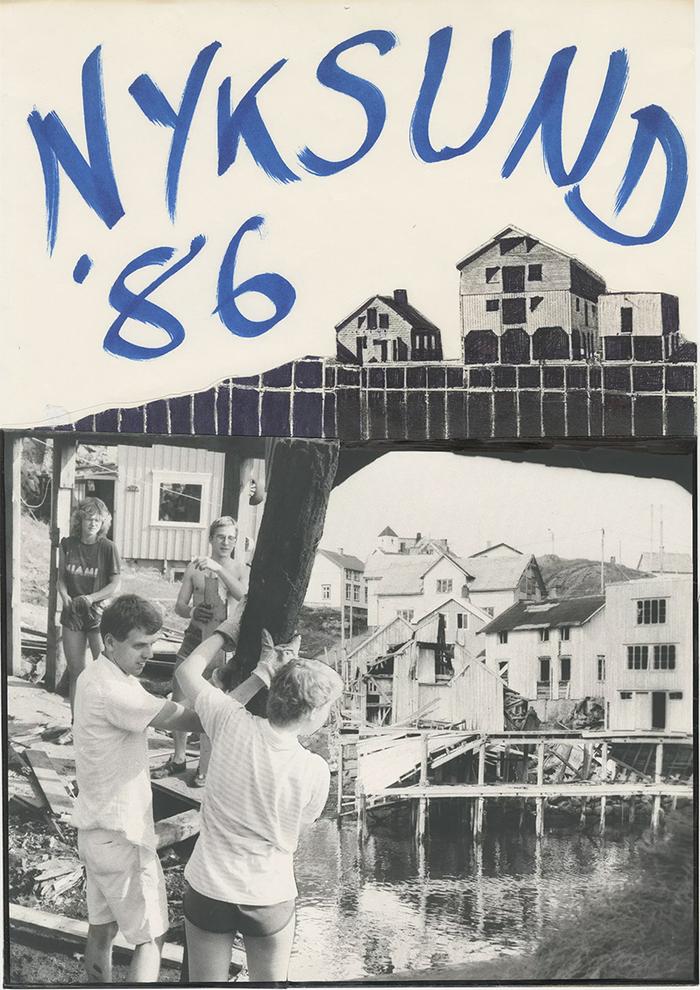

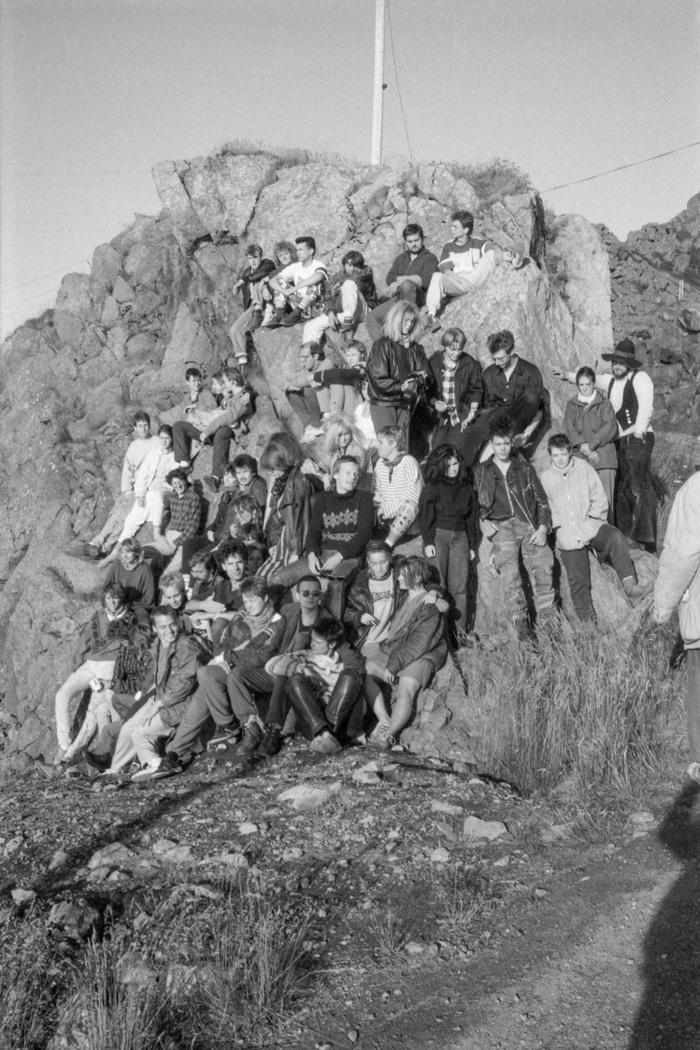

The photos taken by the INP participants from West Berlin, such as Harald Sommer and Carsten Lüring, are charged with fascination for the natural elements of the sub-Arctic north. The analogue photographs radiate with a playful interaction with light: fog, sunsets, backlit mountain tops, and sunbreaks at sea. The participants of the INP engage with elements in front of the camera: nude dips in marshland pits and placing odd objects in the moss. There is little bad weather in the photographs. The vistas are conspicuously held in awe.

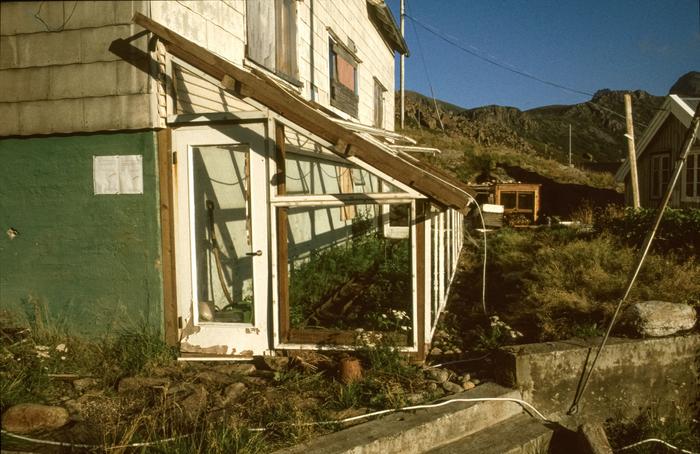

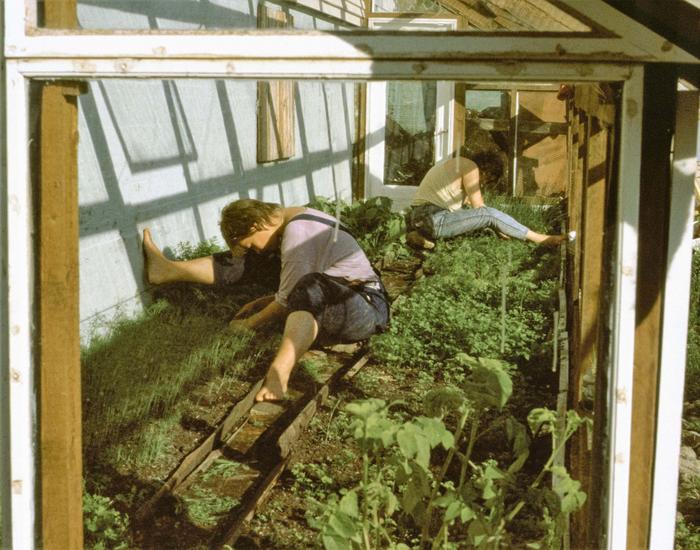

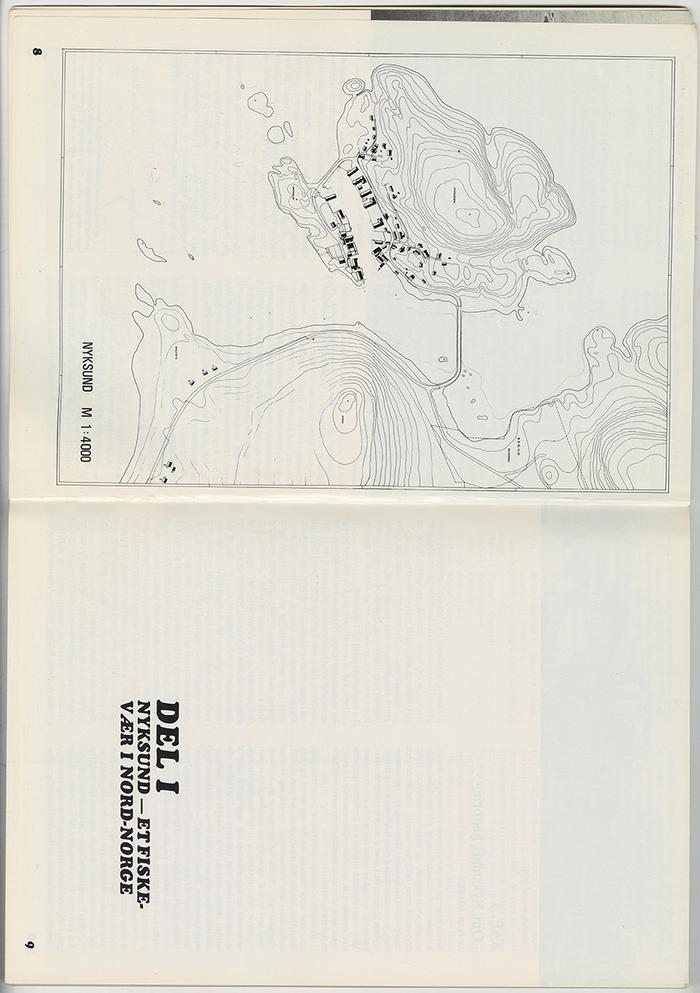

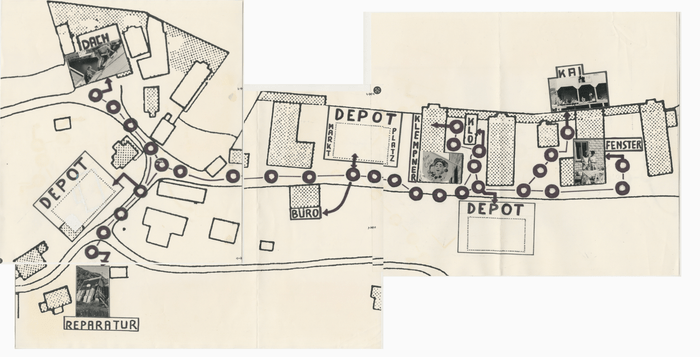

These were also the elements that formed everyday life for Sámi and Norwegian locals who had lived there since before the Viking Age. For them, this was not merely a scenery but the source of food and life-saving knowledge: salting, icing, and drying fish, harvesting feathers, herding reindeer, and collecting berries. Farming in Nyksund was sparse due to the harsh weather, and the rocky headlands and bare islands invited hunting, gathering, and particularly fishing.43 In the late 1800s, Nyksund experienced prosperity from vast herring migrations, followed by cod passing just outside – “on the edge”, på egga – where the seabed steeply descends into the depths of the Norwegian Sea.44

At that time in the region, people’s relationship with the weather and the seasons was of course both intimate and all-important. Embodied knowledge was passed down through generations and taught from childhood, shaping a deep awareness of the environment. Has there been enough sun for the berries to ripen? Is the wind too strong for fishing? Changes in the environment were acutely felt across the entire food chain. Dramatic shifts could lead to poverty or even death. No wonder desires for welfare and social security began to emerge.

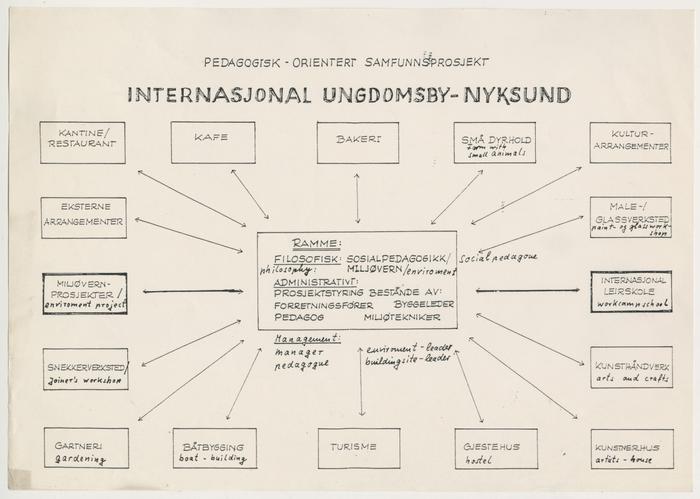

The INP participants, in their way, were also attuned to environmental concerns – pollution and ecological vulnerability were keywords. In a document titled Jahresprogramm 1987, they describe how a stay in Nyksund could foster an understanding of natural cycles and their fragility. They highlighted recent environmental disasters like Sandoz and Chernobyl, the dying forests of southern Norway, oxygen-deprived lakes, and the radioactive effects on sheep and reindeer. “The ozone layer above us is weakened, and the consequence of this will be a change in the Earth’s entire climate balance.”45 Where did these concerns originate? From personal encounters in West Berlin? From smog, a lack of clean air? A longing for the natural elements, for closeness to nature?

Elisabeth Brun, one of the authors of this text, was a kid in Øksnes in the early 1980s. At that time, it was still common for her and other local children to participate in berry picking, potato harvesting, and collective farming duties for the extended family. Meanwhile, traditional handcraft and domestic knowledge was undoubtedly in decline, following society’s structural changes. In the early 1980s, the urbanization of Myre and nearby villages, with their schools, businesses, and services, generated jobs.46 Communications technology was more equally distributed. Brun grew up in a village close to both Myre and Nyksund – in which many of her friends had parents working as teachers or civil servants. Supermarkets provided people with necessities. The welfare society was profoundly present in the region. For young people, sports, television entertainment, and hanging out dominated their spare time. Nature had once directly shaped life in the area, while people’s ties to fisheries and farming were significantly weakened. Still, Brun argues, there remained a sense of nature – a pace inherited – emerging through the daily contact with the elements. A potential, unleashed. An inheritance latent?